The canceled study, which would have employed New Bedford fishermen, is one casualty of $7 billion in clean-energy funding cuts in Democrat-led states.

This story was originally published in The New Bedford Light, a publication partner of Ocean State Stories.

NEW BEDFORD — A research project that would have studied how New England offshore wind projects affect commercial fish species is now dead in the water.

The canceled study, which would have employed New Bedford fishermen, is one casualty of $7.5 billion in clean-energy funding cuts in mostly Democrat-led states, announced last week by the Department of Energy.

Coonamessett Farm Foundation, a Falmouth-based scientific research nonprofit, was awarded $3.5 million by the Energy Department in 2021 to survey commercial fish species in wind farm areas before, during and after construction. The surveys, which were scheduled to begin this year, would have helped fill large information gaps on how wind farms on the Atlantic Coast could affect fished species.

Wind developers already collect this type of data (to varying degrees), but the companies largely keep the data private. The project would have published open-source data, and would have paid a handful of fishermen — most from New Bedford — to assist in the project by towing or deploying specialized survey equipment through the waters in and around the wind leases.

Liese Siemann, a senior research biologist and the lead investigator for the project, said it’s “ironic” the federal government terminated a project that could have provided information to fishermen, a group that’s been vociferous in its concerns about offshore wind. Many local fishermen supported President Donald Trump in the 2024 election because of his opposition to the wind industry.

“The logic of canceling this project that would answer questions [fishermen] have and support a community [the administration] wants to support kind of escapes me,” said Siemann. “We’re not promoting offshore wind; we’re collecting data about offshore wind and trying to better understand potential impacts.”

An excerpt of the Energy Department’s Oct. 2 termination letter to the Coonamessett Farm Foundation, one of 35 programs in Massachusetts that had its funding cut. Source: Coonamessett Farm Foundation

The Energy Department determined the project was not consistent with the administrationʼs policies and priorities, the Oct. 2 termination letter reads, and “does not effectuate the Department of Energy’s priorities of ensuring affordable, reliable, and abundant energy to meet growing demand and/or addresses the national emergency,” as directed by a January executive order.

U.S. Rep. Bill Keating condemned the cuts as “ideologically targeted” and part of an effort spearheaded by Office of Management and Budget head Russell Vought (and Project 2025 co-author) to attack science and research.

He, along with the Massachusetts congressional delegation, has requested communications and other information from the Energy Department and the Office of Management and Budget on their decisionmaking, analysis, and the appeals process.

“The agencies you’d ask these questions of, they’re not staffed right now. The government is shut down right now,” Keating said. “Cynically, the timing of this makes you wonder.”

The Energy Department did not respond to questions and a request for comment.

Before they could set out to sea and start collecting the data, Siemann said they had to test a new piece of gear, build some gear, plan the survey and study design, and deal with permitting and approvals.

In theory, Siemann said, they would have been ready to start the surveys in May of this year, and could have been on their second set of surveys this fall. They decided on collecting data from the waters surrounding three Orsted projects: South Fork Wind (completed), Revolution Wind (under construction) and Sunrise Wind (which has since started construction).

But since January — the start of the second Trump administration — they said the Energy Department, which must give requisite approvals for the project to move forward, went radio silent.

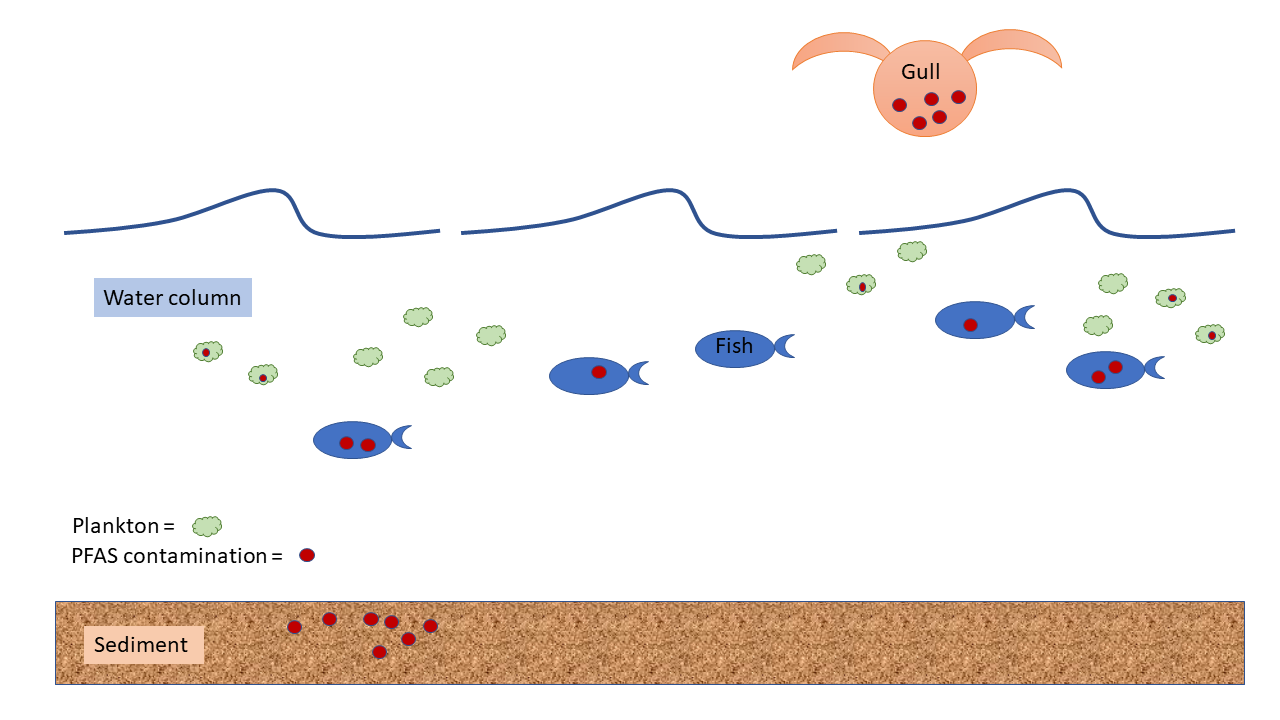

“It leaves a lot of unknowns,” said Justin Potter, director of operations at Coonamessett Farm Foundation, adding the surveys would have informed how species in the wind areas respond to the structures (whether they are attracted to or avoid the turbines, and so on). “It was a large dataset that is no longer going to exist.”

Potter stressed that the data gathered from this project would have been public and was “not going to be controlled by an offshore wind company.”

This type of data is critical and much needed, according to a 2023 report produced by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management in partnership with Responsible Offshore Development Alliance (RODA) — a coalition of fishing groups that has fought offshore wind development.

The report stated “an enormous amount of research is still needed in order to understand the impact of [offshore wind] on our environment and fisheries, but time is limited.”

Capt. Jeff Murray, a New Bedford-based fisherman, wants those answers, which is why he joined the Coonamessett project.

“I was more interested in doing it so I knew the data was correct … so we could see the impact, and that [the data] is not fudged,” said Murray this week while out fishing for sea bass near the Revolution Wind and Sunrise Wind projects.

He said in the last year or two, sea bass fishing has been bad, and that the one change he could think of that might have caused that was the addition of turbines. This project, he hoped, could have helped him to figure it out.

Potter said cooperative projects that involve the fishing community in its data gathering are valuable from a research perspective.

They can also be a source of money for an industry that has been struggling.

Some fishermen have supplemented their income by using their vessels to facilitate the buildout — or in this case, the research — of offshore wind. This research project would have paid between $50,000 and $100,000 a year, Potter said.

“I wanted no part of helping them install these wind turbines,” said Murray, who doesn’t work for wind developers. “But that particular project I wanted to be part of so that I knew that the data was realistic.”

“I don’t understand. They’re letting them put the wind farms in. They keep saying they’re stopping it, they’re stopping it,” Murray continued. “I’m out here every day. I don’t see much stopping going on. I think if they’re gonna do the damage, then we should at least be able to see what the results are.”

Siemann said commercial fishermen “deserve full transparency about how offshore wind development may affect them,” and that this project would have yielded essential data and analysis to improve understanding of that.

Also losing out is UMass Dartmouth’s School for Marine Science and Technology (SMAST), a subcontractor for the project.

Kevin Stokesbury, fisheries scientist and dean of the school, said the news is upsetting. SMAST’s role was to, through non-invasive survey tools, estimate the different fish moving through the area, be it their size or species.

“That’s just information that the fishermen are continually and, rightly so, interested in because these [wind] developments are coming, at least some of them, and you do want to be able to say this shift is a result of natural variation, or a result of the development,” Stokesbury said.

“The overall concern is that anything you do that lowers the amount of information is going to increase the uncertainty and increase the debate,” he continued. “So hopefully what we do with this kind of work is expand our knowledge so we can talk about it factually instead of just different people’s opinions.”

He also pointed to a Trump administration executive order on “restoring American seafood competitiveness,” which in April directed another federal agency, NOAA Fisheries, to incorporate “less expensive and more reliable technologies and cooperative research programs into fishery assessments.” This project was one example of cooperative research with the fishing industry.

The termination letter briefly states that the award recipient may appeal the Energy Department’s termination, which Potter said they are considering.

Coonamessett Farm Foundation’s project is one of 35 in Massachusetts (and 223 nationwide) that have been terminated, and part of more than $450 million in cuts in the state, according to Gov. Maura Healey’s office. Her office said the cuts will harm projects that were working to lower energy costs and build a more reliable grid.

Keating expressed doubt that the state would step in to assist, stating it’s getting “hammered” by federal cuts, including on health care: “There’s no way the Commonwealth can make up for that kind of void. It’s just too big.”

Altogether, Siemann estimates at least 40 people were involved in this project between the foundation, SMAST, other contractors and local fishermen.

“We’re working with a community that’s going to be impacted by offshore wind and who themselves want to understand what the impact is,” Siemann said of their research. “It’s good, it’s necessary and I hope we can find another way to do this.”

Email Anastasia E. Lennon at alennon@newbedfordlight.org.