Passover, also called Pesach, began on April 12, and ends at sundown on April 20.

This story was originally published on April 15, 2024, with a headline noting the dates last year. Its meaning remains relevant in 2025.

— Rabbi Ethan Adler, the religious leader of Congregation Beth David in Narragansett. He also serves Congregation Sharah Zedek in Westerly.

At its core, Passover commemorates the Jewish People’s escape from Egyptian bondage over 3400 years ago. It is celebrated at a special meal, called a Seder, using food items to symbolize the messages of the Biblical narrative. A shank bone represents the ancient sacrifices; bitter herbs remind us of the painful journey of slavery; an egg represents rebirth and hope; a green vegetable provides a glimpse into spring and new beginnings; and a special mixture of apples, honey and walnuts recall the very bricks and mortar used by the Jewish slaves as a they build edifices for the Pharoah, the then ruler of Egypt. In addition, we eat Matzah, unleavened bread, to denote the ‘unleavened’ life of slavery, and we drink wine, epitomizing the sweetness of a longed-for future of autonomy and self-determination.

But more than that, Passover elicits the prospect of celebrating three important ‘Fs’ – Freedom, Faith, Family. Each of these significant notions embody what is at the heart of Judaism. To be able to celebrate holidays without obstruction, without having to hide, without requiring police protection; to sustain our beliefs in whatever we believe in, without having to explain, defend and shield our convictions; to enjoy the company of family and friends, without worrying about what the neighbors might be thinking.

And as we gather for the Festival of Freedom, we are starkly reminded not to “pass over” our traditions, our customs, our way of life. We are encouraged not to “pass over” opportunities to help others, to enjoy the simple gifts of life and to renew ourselves every day.

In a sense, then, the Passover story is a story about us!

— Rabbi Sarah Mack, Senior Rabbi of Temple Beth-El in Providence.

As we approach Passover this year, I find myself struggling with the celebration of this festival of freedom. Our most recent festival observance, Simchat Torah, is still resonant with the horrors of October 7th. There are still Sukkot standing in abandoned communities in the Gaza envelope whose residents fled in the face of Hamas’ brutal attack. Amidst Israel’s struggles and sorrow our hearts also ache at the death and suffering of innocents in Gaza. Continued threats to Jews around the world with the rise of antisemitism is alarming and painful. As days and months continue to pass it is upon us to make meaning, even in challenging times.

In fact, Jewish holidays have helped Jews process trauma through the centuries. The calendar teaches us how to hold joy and grief in our hearts simultaneously. Consider how the Passover Seder tells a sacred tale of degradation to freedom. Like the ancient Israelites we too journey from vulnerability to strength, from despair to hope. In telling the story each year, we are reminded of our power to overcome.

Through sacred texts we can find new meaning for each year— even this year. Rabbi Yehoshua teaches in the Talmud, “In Nisan they were redeemed; in Nisan they will again be redeemed.” Recollection of redemption’s past gives us hope for a redemptive future.

Rabbi Dahlia Marx is a tenth generation Jerusalemite ordained as a rabbi in the Reform Movement who teaches at Hebrew Union College. She asks in her beautiful new volume, From Time to Time, “Mah Nishtanah? Why is this one different? Behind the door to that question hide deeper, more vital questions, whose answers are much less clear: what will we make different? What will we change?”

I write these words with hope in my heart that by the time this is published the remaining hostages will be freed, the temporary cessation in fighting currently on the table agreed upon and some peace and comfort present for all the citizens of the land. Hope is, after all, Passover’s very essence. That is exactly what we mean when we say “Next Year in Jerusalem” at the end of the Seder. Dissatisfaction with the status quo is a very Jewish value. Passover reminds us that transformation originates in our questions and comes to fruition through our actions.

Around our Seder tables we too will ask: “Why is this one different?

“What will we change to bring redemption closer and repair our battered world?”

Let us go forth with optimism and resilience to transform ourselves, our communities and the world for the better with our heads, our hearts and the work of our hands.”

Editor’s note: Rabbi Mack also shared these thoughts this month in her congregation bulletin.

— Rabbi Wayne Franklin, Senior Rabbi Emeritus, Temple Emanu-El in Providence.

Thoughts on Passover, 5784 / 2024.

Passover is one of the primary holidays in the Jewish calendar. It unites nature and history, memory and hope, family and friends, questions and answers. The holiday celebrates the blossoms of springtime as parallels to the birth of the Jewish people at the Exodus from Egypt. The story, which we read at the Seder meal, is known as the Haggadah, Hebrew for “narrative.” Its message rejoices in the fulfillment of God’s promise of redemption to our ancestors. We praise God in appreciation for our people’s deliverance from slavery to freedom, from despair to joy, from mourning to celebration, from darkness to light, and from servitude to redemption. The Seder table features many symbolic foods: bitter herbs help us imagine the harshness of slavery; matza, the bread of poverty, reminds us of the moment of deliverance; fresh vegetables celebrate rebirth in nature and the emergence of our people in freedom.

The Haggadah reminds of us of God’s faithfulness. Not only did God redeem our ancestors from Egypt; God promises to rescue our people when new dangers arise in the future. Along with that optimistic promise, the Haggadah warns that “It is this promise that has sustained our ancestors and us, for not just one enemy has arisen to destroy us; rather in every generation there are those who seek our destruction, but the Holy, Blessed One rescues us from their hands.”

Passover arrives this year at a time of anxiety for Jews. Antisemitism is on the rise, in the United States and in many other parts of the world, which makes this a time of danger for many Jews. As we celebrate Passover this year, we turn again to God seeking protection and security. Many of us believe that the method of the Haggadah – talking, telling our neighbors who we are and the high value we place on life and liberty, can help to overcome ancient stereotypes and destructive myths which still circulate about Jews and Judaism. At our Seder tables, we dream of that Messianic time when people of all religions and nationalities will understand and appreciate each another more fully, recognizing that all of us are inherently equal as human beings. We all can help make that time come closer, by taking our cue from the Passover Haggadah and using the most essential of our human abilities – the power of communication.

— Rabbi Daniel Kripper, Temple Shalom, Middletown.

Pesach – the name by which the Jewish Passover is known – is a singular and transcendental festival. It constitutes an essential and joyful celebration that has, along with its historical context, a sense related to nature. “You shall keep the feast of unleavened bread, for on this same day I brought you out of Egypt, and you shall observe this day throughout your generations by the law forever.” (Exodus 12:17)

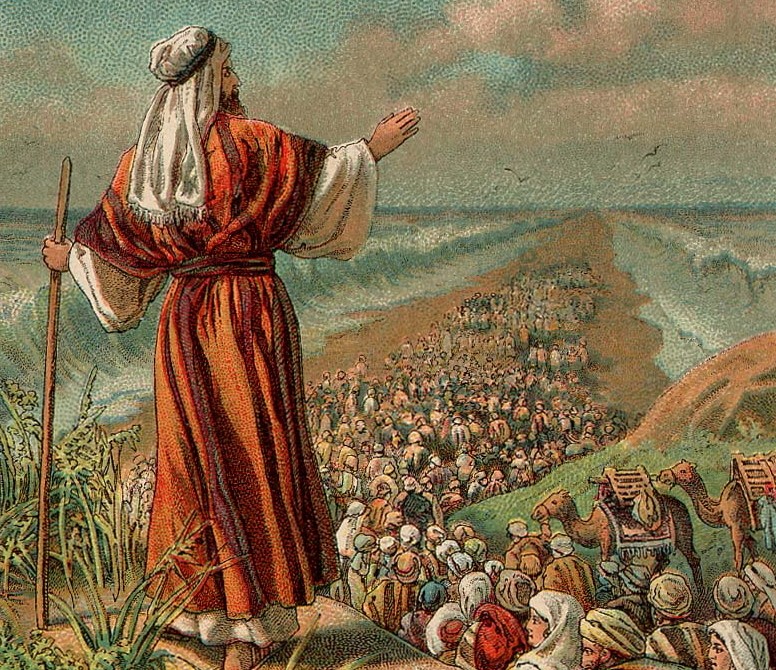

It is not only a symbol of the freedom of the Jewish people guided by the greatest prophet Moses — who, by divine instructions, freed the Jews from slavery in Egypt and led them to the foot of Mount Sinai, where they received the Torah or Divine Teachings — but also celebrates the arrival of spring. Pesach commemorates two transformations: the enslaved person into a free man and the barren soil into a fertile field.

There were three pilgrimage festivals in which the men of the Jewish people came from the most remote places to Jerusalem in the time of the Temples (700 B.C.E. – 70 C.E.): The cycle begins with Pesach, which represented the sowing of the first harvest.

It is considered to be on Pesach when the Jewish people celebrate the anniversary of their birth. The Hebrew people were formed as such in the desert and later arrived in the Land of Israel.

This holiday is a central theme in Jewish tradition, and the liberation from Egypt is remembered daily in various prayers and precepts.

For 430 years (Exodus, 12:40), the Jews were enslaved people in Egypt. The redemption did not happen suddenly. According to the accounts in the biblical narrative, it was preceded by a long and arduous evolutionary process. Time and again, Moses intervened before Pharaoh. They intended to leave with the Egyptian’s approval. Again and again, Pharaoh frustrated these diplomatic attempts. Finally, on the 15th day of the Jewish month of Nisan, more than 600,000 men and women left Egypt and began their journey through the desert. Near the Red Sea, Egyptian battalions made their last attempt to capture the lost enslaved people and failed. After the miraculous crossing of the Red Sea, Moses and all the people of Israel sang a song of gratitude and praise to God.

The redemption of the Jews was an essential stage that culminated with the reception of the Tablets of the Law, which contain the Ten Commandments, precepts that guide the Jewish people and form the basis of the three major monotheistic religions.

The exodus of the Jews from Egypt more than 3,000 years ago defined their national identity. It marked their birth as a nation and free people, giving foundation to the Jewish faith and ethics, which have freedom as their fundamental value. The tradition suggests that every man should consider himself as if he had left Egypt.

Pesach is celebrated every year on the 14th of the month of Nisan, which coincides with the first days of spring. It is a time of fruitfulness and renewed hope for the future where man, in communion with nature, celebrates the renewal of life. For an exclusively agricultural and cattle-raising people like the Hebrews of that time, Pesach sealed a symbol with nature.

The most characteristic feature of the celebration is the consumption of matzah, an unleavened bread or cracker prepared only from wheat and water, representing the bread eaten by the Jews as they left Egypt. The matzah is also called the “bread of poverty” because besides keeping awake in every Jew the memory of the times of oppression in Egypt, it induces him to watch over the rights of others and help people in need.

For eight days, Jews may not eat or possess any food containing leaven. Every Jewish home must be cleaned on the eve of the Festival to remove all traces of leavened food. Changing dishes and kitchen utensils is customary to comply with the precept.

During the first night of Pesach (outside of Israel, during the first two nights), Jewish families gather in their homes and hold a dinner called Seder. The word Seder means order and refers to a religious service that includes a festive meal and a specific ritual that differentiates it from other dinners. It is full of symbols and millenary traditions whose purpose is to relive the experiences of slavery, exodus, and freedom and to pass them on to future generations.

The Seder night shines with the symbolic elements that compose it extraordinarily. It invites adults to reflect and children to question. The biblical precept conditions its liturgy, “You shall tell your son on this night, saying: God has brought me out of Egypt.” The Pesach Haggadah is read, a small book that tells the story of the departure from Egypt. It tells the old and ever-new tale of the Hebrew people, their redemption, and their survival. In addition to including the order of the dinner, it contains joyful songs, psalms, and blessings.

This celebration includes a special prayer for those who lack freedom and those prevented from celebrating the occasion.

It is for them, for people who are held in captivity, for those who are persecuted for wanting to practice their traditions and their ancestral culture, for all those who struggle tirelessly to live with dignity, that in every Jewish home, beats hope that one day soon they will be able to join the great family of free men.

In its most extraordinary celebration, the people do not forget the poverty and bitterness, past and present. The heart opens then in a supreme desire to embrace all the helpless of the world.

The evening concludes with the traditional words, ‘Next year in Jerusalem!’ Amid the sorrows and tribulations of the present, we do not cease to ‘pray for the peace of Jerusalem’ and the good coexistence in the Middle East.”

Editor’s note: This is the latest in a series of Ocean State Stories’ explorations of significant events in various religions. Previously, we wrote about Christmas and Ramadan.